Mary Ellen Bute 1906-1983

Bute and Nemeth

by Sandra Naumann

Living in a time where audiovisual art works are omnipresent, it is important to trace back the roots of the idea of merging sound and vision, an art form that remains particularly male dominated. It is essential to show how women were and are shaping this development. A prime example thereof is Mary Ellen Bute whose work can serve as a role model for contemporary female audiovisual artists.

Even though Bute undertook a lot of pioneering work in avant-garde film, and greatly succeeded in her time, she today remains little recognized compared to her male counterparts. Bute is rarely mentioned in film encyclopedia, and if so, only in passing and with perpetually wrong dates and facts.

Born in 1906, Mary Ellen Bute went to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts to study painting but soon found this art form too restricting. Searching for a kinetic art of light she started to explore the possibilities of light instruments, traveling through Europe and assisting color-organ inventor Thomas Wilfred with his “Hall of Light”. In 1931 she continued her research on the electronically transformation of acoustical into optical signals with Leon Theremin and on mathematical concepts of composition with Joseph Schillinger. After discovering celluloid as an ideal medium she completed her first film “Rhythm in Light” which premiered in the Radio City Music Hall in 1935 and is probably the first publicly shown American abstract film.

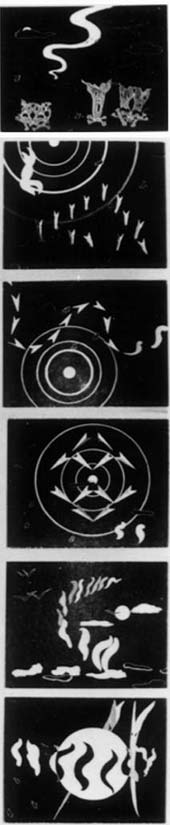

For this black and white film Bute arranged drawn images with filmed pictures of every day objects such as ping-pong balls and egg-beaters, which lost their representational character through multiplication and distortion and produced an appealing play of light and shadow. With the support of her later husband Ted Nemeth she went on to produce a series of films synchronizing abstract imagery to pieces of popular music. After refining the black-and-white-techniques she turned to early color-film-systems and extended her visual language to animation techniques like frame-by-frame-drawings and superimposition. In the early 1950’s along with Norman McLaren and Hy Hirsh Bute was among the first artists to explore electronic imagery in film. The use of oscilloscope patterns she regarded as the direct and most physical visualization of sound as well as a unique fusion of art and science.

Switching to feature films with “Passages from Finnegans Wake” Bute was the first to adapt a work of James Joyce and was honored for this project at the Cannes Film Festival in 1965 as best debut. Later projects remained uncompleted because she couldn’t raise enough funding.

In 1978 Bute was a founding member of the Women Independent Film Exchange, a foundation trying to organize women against the discrimination of female artists and to re-discover the contribution of women in early American film history. Spending the last years of her life in a Salvation Army residence in New York she died impoverished in 1983.

Bibliography

*Basquin, Kit: Energy in Motion, in: Angles. Women Working in Film and Video, Milwaukee, Vol.3, No.3,4, Spring 1988, pp.24-25.

*Batten, Mary: Actuality and Abstraction. The Cinematic Use of Scientific Machines, in: Vision. A Journal of Film Comment, New York, Vol.1, No.2, Summer 1962, pp.55-59.

*Beckerman, Howard: “Animation Spot,” Backstage November 11, 1983.

*Bute, Mary Ellen: Abstronics: An Experimental Filmmaker Photographs the Esthetics of the Oscillograph, in: Films in Review New York: National Board of Review of Motion Pictures, No.5, June-July, 1952, pp.263-266.

*Bute, Mary E., “Light * Form * Movement * Sound”, in: Design 42, o.O., * *Bute Mary Ellen: (interview), AFI Report, Washington DC: American Film Institute, Summer 1974No.8, April 1941, p.25

*Bute, Mary Ellen: “The Emergence of Abstract Film in America”, Articulated Light Boston: Harvard Film Archive, 1995.

*Jacobs, Lewis: Experimental Cinema in America, 1921-1947, Hollywood Quartely, Vol.3, No.2, Winter 1947/48, pp.111-124, reprinted as “Avant-Garde Productionin America” in: Manvell, Roger: Experiment in the Film, London 1949, pp.278-292.

*Markopoulos, Gregory: Beyond Audio Visual Space. A Short Study of the Films of Mary Ellen Bute, in: Vision. A Journal of Film Comment, New York, Vol.1, No.2, Summer 1962, pp.52-54.

*Moritz, William: Seeing Sound, in: Animation World Magazine, 1.5.1996.

o.V.: Mary Ellen Bute [Interview], in: American Film Institute Newsletter, Washington, D.C., Vol.5, No.2, 1974, pp.40-41.

*Rabinovitz, Lauren: Mary Ellen Bute, in: Horak, Jan-Christopher: Lovers of Cinema. The First American Film Avant-Garde 1919-1945, 1995, pp. 315-334.

*Schiff, Lillian: The Education of Mary Ellen Bute, in: Film Library Quarterly, New York, Vol.17, No.2,3&4, 1984, pp.53-61

*Schillinger, Joseph: Excerpts from a Theory of Synchronization, in: Experimental Cinema, New York, No.5, 1934, pp.28-31.

*Weinberg, Gretchen: An Interview with Mary Ellen Bute on the Filming of “Finnegan’s Wake”, in: Film Culture, New York, No.35, Winter 1964/65, pp.25-28